Between Tradition and Innovation: A Pathway for Traditional and Complementary Medicine in Singapore’s Evolving Healthcare System

Abstract

In step with a growing global appetite for traditional and complementary medicine (T&CM), there has been a renewed interest in the development of similar alternative medicine in Singapore’s healthcare system. This is especially so with the implementation of the Healthier SG initiative. However, gaps in the regulation of T&CM continue to exist while sceptics doubt the place of T&CM in the evolving healthcare landscape. Seeing that T&CM is a potential boon in Singapore’s future healthcare system, this article first seeks to investigate the role and functions of T&CM in modern healthcare systems. It will do so by looking to the experiences of other foreign healthcare systems, before turning inward to survey the challenges in carving out a place for a mature practice of T&CM in Singapore. Finally, the article concludes by attempting to uncover a path for a more holistic and effective integration of T&CM into the mainstream healthcare system.

I. Introduction

Traditional and complementary medicine (T&CM) is a composite term that captures medical practices with two distinct characteristics. On the one hand, they are “traditional”; they evolve out of a specific culture’s unique knowledge, skills, and practices, whether scientifically understood or not[1]. On the other hand, they are “complementary”; they are not part of the country’s mainstream medicine[2].

Seen today as a branch of healthcare that “has many contributions to make”3, recognition and adoption of T&CM has come a long way since the Declaration of Alma-Ata4 – a 1978 document that established primary health care as the key to achieving “Health for All” – first called for its inclusion in primary healthcare systems. Indeed, in its Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2019, the World Health Organisation (WHO) reported an almost fourfold increase in the number of Member States with a national policy on T&CM between 1999 and 2018. Specifically, Southeast Asia fared “better than the global averages on all indicators” due to its “historical systems of traditional medicine…and a strong policy focus”5. Singapore has not deviated from this regional trend, especially with regard to her use of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)6. In 2024, one in five Singaporeans were seeing TCM practitioners7. Since the commencement of the Healthier SG initiative in 20238, TCM has also been recognised as a preventive care strategy that should “have a role in Healthier SG”9, considering the initiative’s focus on preventive health.

Signs of inertia towards T&CM, however, continue to abound. In 2019, WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus noted that T&CM is “often underestimated”10. Meanwhile, in Singapore, wider public recognition of T&CM continues to face “many hurdles”11 as “sceptics…treat TCM and other traditional medical practices with suspicion”12. Therein lies a conundrum: if there are benefits to adopting T&CM13, why has this not been reciprocated with an equally enthusiastic response towards its practical integration with mainstream medicine?

Therefore, in what follows, I begin by considering the role and functions of T&CM in modern healthcare systems by unpacking what “integration” in the context of T&CM entails. I then adopt this conceptual framework to locate Singapore’s current position and the position it aspires to arrive at in relation to T&CM integration. Thereafter, I look to foreign jurisdictions to identify successful strategies and consider how they can be applied in Singapore to overcome obstacles obstructing wider T&CM adoption. In turn, it will be argued that the key deficiency in T&CM integration is not the inclusiveness of Singapore’s healthcare system. Instead, the central issue is the lack of interaction and communication between conventional biomedical providers and T&CM practitioners.

II. The Role of T&CM in Modern Healthcare Systems

I begin by considering the meaning of “integration” in the context of T&CM. Scholars have sought to unpack the term in various ways14, two of which are considered here.

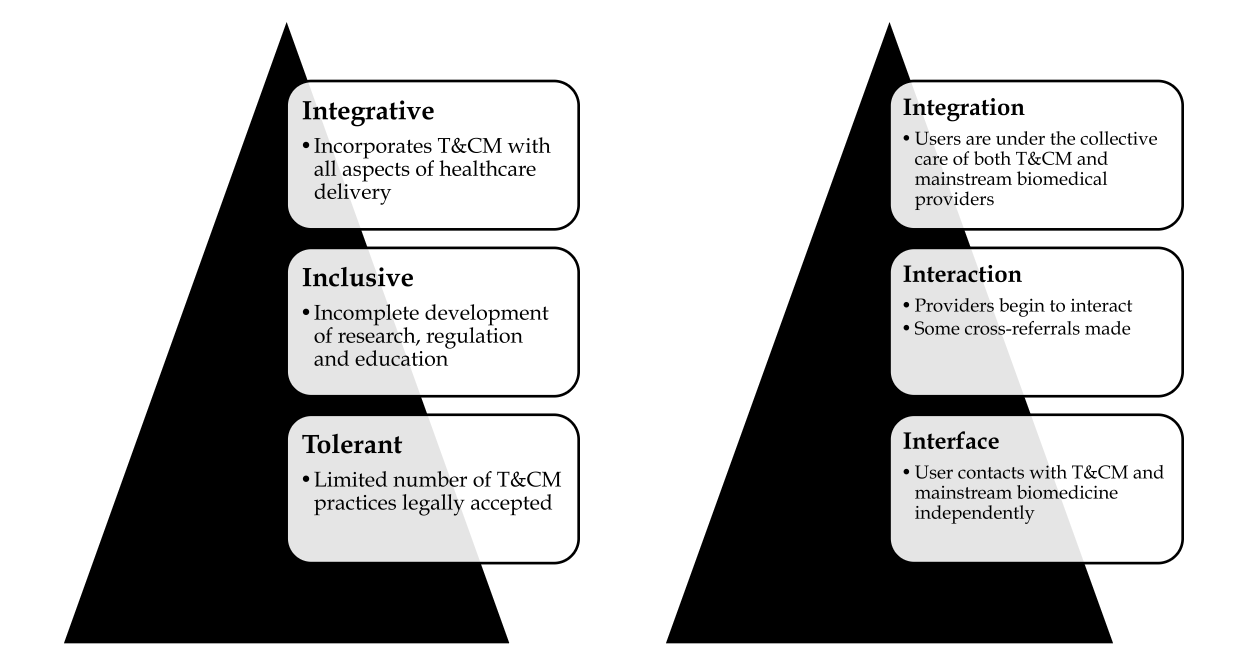

First, integration can be understood from the policy dimension (Figure 1.1)15. Under this conception, healthcare systems can be described as “tolerant”, “inclusive” or “integrative”, depending on the degrees to which they recognise T&CM. A “tolerant” healthcare system operates entirely on biomedicine, although a limited number of T&CM practices are legally accepted. In becoming “inclusive”, a healthcare system begins to recognise T&CM practices as a parallel mode of healthcare service delivery. There might be some referrals between T&CM and conventional biomedicine, although developments relating to the research, regulation and education of T&CM practitioners are not complete. Finally, an “integrative” healthcare system incorporates T&CM with all aspects of healthcare delivery, including research, policy, insurance, regulation, education and services.

Second, integration can also be understood from the user’s perspective (Figure 1.2)16. This conception considers how users and practitioners integrate T&CM treatment in practice. On this view, assimilation can be at either the “interface”, “interaction” or “integration” levels. At the “interface” level, the user contacts with T&CM and mainstream biomedicine independently. The user exclusively bears the burden of integrating T&CM and conventional biomedicine in their treatment, and may only disclose little information from one provider to another. At the “interaction” level, providers begin to interact, making cross-referrals while users share information between providers. At the “integration” level, users are under the collective care of both T&CM and mainstream biomedicine providers. Both teams of providers operate in partnership and it is this collaboration that drives the integrative care provided to the user.

Given the above, where does Singapore currently lie on both scales, and where does the country aspire to lie?

Figure 1.1. Integration on policy front. Figure 1.2. Integration from user’s perspective.

A. The current position

(i) On the policy front

Singapore’s system currently seems to be “inclusive” on the policy front. After the Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioners Act was passed in 2000, acupuncture was legalised in public hospitals and nursing homes in 2005 and some TCM clinics were co-located within public healthcare institutions17. In some instances, public hospitals also began to incorporate acupuncture as part of their patient pain management care pathway18. Today, the Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Grant19 and Traditional Chinese Medicine Clinical Training Programme20 continue to direct consistent capacity building efforts towards further maturation of the T&CM ecosystem in Singapore.

Therefore, to characterise Singapore’s T&CM policies as merely “tolerant” would be unfair. Equally, however, to say that Singapore’s current system is “integrative” seems to go too far. Gaps continue to exist: as of 2023, 5.2% of registered TCM practitioners continue to operate without any formal qualifications21 and Singapore’s first locally conferred Chinese Medicine undergraduate degree programme only began enrolling its first batch of students in 202422. Furthermore, it was only in December 2020 that a trial was launched to extend subsidy and Medisave coverage to support TCM acupuncture at specialist outpatient clinics in public healthcare institutions23. Therefore, while Singapore has begun to recognised T&CM as a parallel mode of healthcare delivery, development of T&CM research, education and regulation remains incomplete (Figure 1.1).

(ii) From the user's perspective

As regards the level of integration from the user’s perspective, the Minister for Health observed24:

In fact, this [the choice to seek out both T&CM and traditional biomedicine] is a decision not for the government or Western doctors to take. It is already decided by many Singaporeans, who are choosing TCM.

This suggests that, from the user’s perspective (Figure 1.2), T&CM is currently at the “interface” level; complementary TCM treatment continues to be sought by healthcare users themselves instead of being managed by “the government or western doctors”. Perhaps more revealingly, two past studies confirm the Minister’s observations as to the lack of interaction between T&CM and conventional biomedicine, even as Singaporeans utilise both: in the one, 70% of Singaporean breast cancer patients were found to not disclose their TCM use to their Western medicine doctors25, while in the other, 74% of Singaporean T&CM users26 reported likewise.

B. The Aspiration

(i) On the policy front

On the policy front (Figure 1.1), the Health Minister outlined his vision as follows27:

The approach therefore must be selective inclusion, based on evidence. We should avoid a mindset or mentality of wholesale inclusion or wholesale rejection of TCM. That would be most unwise28.

Policy-wise, therefore, the aspiration seems neither to be a fully “integrative” or a “tolerant” system, given how the Minister preferred “selective inclusion”. Instead, given the differences between T&CM and conventional biomedicine and the deep entrenchment of biomedicine in Singapore healthcare system, Singapore’s aspiration seems to be towards an “inclusive” (or at most quasi-integrative) system. This aspiration seems to resemble what has already been achieved. Indeed, given current efforts to address the regulation, practice, health insurance coverage, research and education of T&CM, there are likely fewer gaps on the policy front now.

(ii) From the user's perspective

As regards integration from the user’s perspective (Figure 1.2), however, the following was suggested29:

Conceptually, the patient can be referred by TCM practitioners to a GP (general practitioner) for fully subsidised vaccinations and screenings, and chronic disease management, while continuing with TCM care, including receiving support on adjusting their lifestyles. Both can happen at the same time – TCM and GPs can work together, to make sure patients are healthy.

The approach here seems to lie at the “interaction” level and may even contain certain elements of “integration”. Particularly, instead of the user, it is now the T&CM and conventional biomedical practitioners who drive the interactions between the two medical disciplines, as they “work together” and operate in a system of referrals.

Two observations can be made from the above comparisons between Singapore’s current position and that which the country aspires towards. First, the current level of T&CM integration at policy level is higher than that from the user’s perspective. Indeed, even while there are emerging and continued efforts to foster a constructive environment for the integration of T&CM with conventional biomedicine, it is the users themselves who continue to drive integration on the practical front. The lack of institutional communication, cross-referrals and the like continue to be absent30. Second, and relatedly, we observe the need for greater integration from the user’s perspective. Much more is therefore required to address the inadequate interaction and communication between conventional medical professionals and T&CM practitioners.

III. Lessons and Proposals

Given the above gaps, we now turn to consider strategies for an increased integration of T&CM. In a particular attempt to address the inadequate interactions and communication between conventional biomedical providers and T&CM practitioners, three proposals are discussed:

- Improving interprofessional education;

- Enhancing integrated healthcare facilities; and

- Establishing a shared electronic health record system.

While these strategies are not exhaustive, they are appropriate candidates for discussion here for three reasons. First, these are practices which have been mooted in other healthcare jurisdictions and have achieved success. Second, the proposals are feasible strategies given that it will be demonstrated that Singapore already possesses a strong foundation to institutionalise them. Third, they are good examples of specific initiatives fostering improved interaction and communication between T&CM and conventional medical providers; they can therefore serve as good springboards to imagine further steps.

A. Improving Interprofessional Education

Interprofessional education refers to having “two or more professions learn with, from and about each other to improve collaboration and the quality of care”31. In the context of T&CM integration, interprofessional education is essential to provide a broader range of opportunities for both conventional medical professionals and T&CM practitioners to build trust and enhance collaboration32. China, for example, has established a strong pipeline of interprofessional education33. By 2015, there were more than 200 Western medicine or non-medical institutions of higher learning offering programmes in TCM, enrolling some 752,000 students. Concurrently, modern medicine courses continue to be offered at TCM colleges and universities to train practitioners who possess a good understanding of both T&CM and conventional biomedicine.

Compared to China, interprofessional education in Singapore is less developed. In 2019, it was reported that 35% of Western medical practitioners do not discuss the usage of TCM with their patients34. This is surprising, given that concurrent Chinese herbal medicine and Western medicine prescription drugs consumption was found to occur in close to 63% of Singapore patients35. This disparity seems to be attributed to the lack of understanding of TCM on the part of Western medical practitioners: not only do they lack formal education on TCM, only about 10% of them have personal experience in using TCM36. It is therefore understandable why more than 70% of Western medical practitioners feel that improving their knowledge of TCM can help themselves and their patients discuss TCM more comfortably37. In this regard, further emphasis should be placed on institutional cross-training between T&CM practitioners and Western medical providers. There are also opportunities to grow existing small-scale offerings like the Graduate Diploma in Acupuncture – a programme that is specially designed by the Singapore College of Traditional Chinese Medicine for registered Western medical doctors and dentists in Singapore38.

B. Enhancing Integrated Healthcare Facilities

The institutionalisation of integrated healthcare facilities may also provide further opportunities for enhanced interactions and communication between conventional biomedical providers and T&CM practitioners. The Royal London Hospital for Integrated Medicine (RLHIM)’s approach is instructive here. Apart from having an Education Department running courses in integrated medicine for registered health professionals39 and a Research Department specialising in integrated medicine approaches to health40, the RLHIM also boasts an integrated pharmacy service staffed by pharmacists specialising in complementary medicines41. Furthermore, the RLHIM provides advice on the safe use of complementary therapies42. In all, the RLHIM integrates both function and expertise: not only is research, education and treatment housed under one facility, the facility thrives on a deep subject-based understanding of both conventional biomedicine and T&CM.

The RLHIM is therefore a good exemplar for Singapore, considering how the country has planned to create Regional Healthcare Systems (RHS) – geographically-defined healthcare ecosystems that bring together primary, acute and community care sectors to collaborate in delivering comprehensive and holistic healthcare services43. In this regard, there is also scope to build on the pre-existing arrangements in several public hospitals to offer acupuncture services, and especially with Tan Tock Seng Hospital (which is already providing cupping and TCM medicinal herbs) and Khoo Teck Puat Hospital (which already offers cupping today)44.

C. Establishing a Shared Electronic Health Record System

Finally, a shared electronic health record system between conventional and T&CM healthcare providers may also prove to be more essential as T&CM gradually entrenches itself within the Singapore healthcare system. Currently, while the National Electronic Health Record (NEHR) is not new, about 30% of private clinics providing conventional biomedical healthcare services and all private hospitals are still not part of the system as of 202445. Records of T&CM treatment are also excluded46. Coupled with large proportions of Singaporeans who choose not to disclose T&CM usage with their Western medical practitioners, this exclusion from the NEHR poses challenges for T&CM integration and may lead to inefficiencies, leaving providers unable to advise patients on best practices to avoid negative herb-drug interactions47.

While there are still challenges to the informatisation of T&CM data due to the lack of standardisation in terms of universally agreed upon practices and quality controls, there is value in beginning to consider and explore the range of standards and datasets which are gradually being introduced to describe T&CM clinical diagnosis and treatment activities48. Korea, for example, has formally integrated traditional Korean medicine (TKM) into the Korean national health system and monitors the use of TKM through a central computerized system. This system boasts not only a comprehensive account of an individual’s health risk factors and lifestyle data, it is also beginning to integrate National Health Nutrition Survey and health check-up results49. The data infrastructure also includes the Drug Utilisation Review – a “world-class pharmacovigilance system” – that tracks in real-time an individual’s drug consumption history to avoid contraindications, negative interactions between different drugs and ingredient duplication50. This comprehensive range of electronic healthcare data integration can serve as a useful reference point for Singapore as it continues to grow the breadth of its NEHR regime. Furthermore, given how big data – data sets which can be processed with advanced analytics tools for the purposes of data exploration, prediction and generalisation – has been used since 2015 in multiple Singapore public medical institutions51, the country seems to be in a good position to expand its use of data to create a system similar to that used with TKM.

IV. Conclusion

The levels of T&CM integration at both the policy level and from the user’s perspective have been considered in this paper. By comparing Singapore’s current position and the country’s aspiration on both scales, I have sought to argue that the key deficiency in T&CM integration does not lie in the inclusiveness of Singapore’s healthcare system and its associated policies. Rather, the larger issue is the inadequate interaction and communication between conventional biomedical providers and T&CM practitioners. It is this factor that accounts for the gap between the current “interface” level of integration and the aspired “interaction” level of integration (Figure 1.2). In response, this paper has surveyed three strategies – improved interprofessional education, enhanced integrated healthcare facilities and the establishment of a shared health record system for T&CM – and outlined how they may serve as possible remedies.

The article has proceeded on the assumption that the aspiration put forth by the Ministry of Health is the appropriate level of integration on both the policy and user experience front. Whether this assumption holds is a topic for another day. But regardless of whether the long-term aspiration has indeed been set desirably, it suffices here to observe that given how the level of integration for the user currently lags behind the level of integration on the policy front, more work must first be done to close the gap. Indeed, even if the level of integration on the policy front is pitched higher (i.e. at the “integrative” level in Figure 1.1), little will translate into actual practice if the level of integration in terms of the user experience remains stagnant. Hence, the argument that more must be done to promote integration from the user’s perspective holds.

From a wider perspective, therefore, the integration of T&CM represents a broader – and indeed important – move for Singapore to advance beyond its traditional disease-centric provision of services within the hospitals towards one focussing on prevention, primary care and community-based management52. The lessons gleaned from the integration of T&CM therefore have larger implications as we seek to integrate healthcare service delivery in more ways to support improved health and wellbeing outcomes under the Healthier SG initiative53. In this regard, T&CM will necessarily have much to contribute as we seek to bring together unconnected streams of healthcare provision and create a unified preventive healthcare ecosystem.

[1] WHO Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2019’ (World Health Organisation, 2019) 8 https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/312342/9789241515436-eng.pdf?sequence=1 accessed 24 November 2024

[2] Ibid.

[3] ‘The Regional Strategy for Traditional Medicine in the Western Pacific (2011–2020)’ (World Health Organisation, 2012) 3 https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/207508/9789290615590_eng.pdf?sequence=1 accessed 24 November 2024.

[4] Declaration of Alma-Ata’ (World Health Organisation, 1978) https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/347879/WHO-EURO-1978-3938-43697-61471-eng.pdf?sequence=1.

[5] These indicators evaluated the degree of adoption of T&CM in Member States and considered, inter alia, factors like the number of Member States within the region with national or state level laws or regulations for T&CM, the number of Member States with national policies on T&CM and the number of Member States with an expert committee for T&CM.

[6] Although it is recognised that TCM is not the only form of T&CM practised in Singapore, the examples used in this paper will relate exclusively to TCM because it is the most used in Singapore, partly due to the large proportion of Chinese in the national population.

[7] Nadine Chua, ‘Traditional Chinese medicine could play a role in Healthier SG: Ong Ye Kung’ The Straits Times (Singapore, 28 October 2024).

[8] Amelia Teng, ‘About 67,000 people have signed up for Healthier SG since registration started’ The Straits Times (Singapore, 9 July 2023).

[9] Nadine Chua, ‘Traditional Chinese medicine could play a role in Healthier SG: Ong Ye Kung’ The Straits Times (Singapore, 28 October 2024).

[10] WHO Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2019’ (World Health Organisation, 2019) 5 https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/312342/9789241515436-eng.pdf?sequence=1 accessed 24 November 2024

[11] Goh Chye Tee, ‘Commentary: Where does traditional Chinese medicine fit into Singapore’s healthcare reform plan?’ Channel News Asia (Singapore, 29 November 2022)

[12] Kathryn Muyskens, ‘Commentary: If TCM really works, why are some still sceptical about it?’ Channel News Asia (Singapore, 20 May 2024).

[13] See, for example, Rogier Hoenders, ‘A review of the WHO strategy on traditional, complementary, and integrative medicine from the perspective of academic consortia for integrative medicine and health’ (2024) Frontiers in Medicine; Jeremy Y. Ng and others, ‘Traditional, complementary, and integrative medicine and artificial intelligence: Novel opportunities in healthcare’ (2024) Integrative Medicine Research; and Wen Qiang Lee and others, ‘Factors influencing communication of traditional Chinese medicine use between patients and doctors: A multisite cross-sectional study’ (2019) Journal of Integrative Medicine 396.

[14] See, for example, Stephen Shortell and others, ‘Creating Organized Delivery Systems: The Barriers and Facilitators’ (1993) 447.

[15] WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy 2002-2005’ (World Health Organisation, 2002) https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/67163/WHO_EDM_TRM_2002.1_eng.pdf?sequence=1 accessed 24 November 2024

[16] Vivian Lin and others, ‘Interface, interaction and integration: how people with chronic disease in Australia manage CAM and conventional medical services’ (2014) Health Expectations 2651.

[17] National Cancer Centre Singapore, ‘Acupuncture scoring points with hospital patients’ https://www.nccs.com.sg/news/patient-care/acupuncture-scoring-points-with-hospital-patients-skh accessed 24 November 2024.

[18] Sin Yee Chew, ‘Challenges and Opportunities in the Practice of Chinese Medicine in Singapore’ (2024) Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine 483.

[19] Ministry of Health, ‘Traditional Chinese Medicine Research Grant’ https://www.moh.gov.sg/others/research-grants/tcm-research-grant accessed 24 November 2024.

[20] Ministry of Health, ‘Traditional Chinese Medicine Clinical Training Programme’ https://www.hpp.moh.gov.sg/all-healthcare-professionals/programmes/ProgrammeDetails/traditional-chinese-medicine-clinical-training-programme accessed 24 November 2024.

[21] ‘Annual Report 2023’ (Traditional Chinese Medicine Practitioners Board, 2023) https://www.healthprofessionals.gov.sg/docs/librariesprovider12/publications/tcmpb_annual-report-2023sep_pdfa.pdf?sfvrsn=11f86388_1 accessed 24 November 2024.

[22] Lee Li Ying, ‘NTU to offer new TCM degree programme in August 2024’ The Straits Times (Singapore, 15 November 2023).

[23] Sin Yee Chew, ‘Challenges and Opportunities in the Practice of Chinese Medicine in Singapore’ (2024) Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine 483.

[24] Ong Ye Kung, ‘Speech by Minister for Health’, (Public Free Clinic Society’s 50th Anniversary Charity Dinner, Singapore, 27 October 2024) https://www.moh.gov.sg/newsroom/speech-by-mr-ong-ye-kung--minister-for-health--at-public-free-clinic-society-s-50th-anniversary-charity-dinner--27-october-2024 accessed 24 November 2024.

[25] Kar Yong Wong and others, ‘TCM Usage in Breast Cancer Patients’ (2014) Annals Academy of Medicine 74.

[26] MK Lim and others, ‘Complementary and alternative medicine use in multiracial Singapore’ (2005) Complementary Therapies in Medicine 16.

[27] Ong Ye Kung, ‘Speech by Minister for Health’, (Public Free Clinic Society’s 50th Anniversary Charity Dinner, Singapore, 27 October 2024) https://www.moh.gov.sg/newsroom/speech-by-mr-ong-ye-kung--minister-for-health--at-public-free-clinic-society-s-50th-anniversary-charity-dinner--27-october-2024 accessed 24 November 2024.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] See, for example, Wen Qiang Lee and others, ‘Factors influencing communication of traditional Chinese medicine use between patients and doctors: A multisite cross-sectional study’ (2019) Journal of Integrative Medicine 396.

[31] UK Centre for the Advancement of Interprofessional Education, ‘About CAIPE’ https://www.caipe.org accessed 24 November 2024.

[32] Timothy Culbert and Karen Olness, ‘Integrative Pediatrics’ (Oxford University Press, New York 2010) 93.

[33] WHO Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine 2019’ (World Health Organisation, 2019) https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/312342/9789241515436-eng.pdf?sequence=1 accessed 24 November 2024.

[34] Wen Qiang Lee and others, ‘Factors influencing communication of traditional Chinese medicine use between patients and doctors: A multisite cross-sectional study’ (2019) Journal of Integrative Medicine 396.

[35] Chester Yan Jie Ng and others, ‘A multi-center cross-sectional study of Chinese Herbal Medicine-Drug adverse reactions using active surveillance in Singapore’s Traditional Chinese Medicine clinics’ (2024) Chinese Medicine 19.

[36] Ibid. [37] Ibid. See also Dietlind L. Wahner-Roedler and others, ‘Physicians’ Attitudes Toward Complementary and Alternative Medicine and Their Knowledge of Specific Therapies: A Survey at an Academic Medical Center’ (2006) Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 495.

[38] Singapore College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, ‘The History of Singapore College of Traditional Chinese Medicine’ https://www.singaporetcm.edu.sg/en/about_history.php accessed 24 November 2024.

[39] University College London Hospitals, ‘Education department (RLHIM)’ https://www.uclh.nhs.uk/our-services/find-service/integrated-medicine/education-department-rlhim accessed 24 November 2024.

[40] University College London Hospitals, ‘About RLHIM’ https://www.uclh.nhs.uk/our-services/our-hospitals/royal-london-hospital-integrated-medicine/about-rlhim accessed 24 November 2024.

[41] University College London Hospitals, ‘Integrated medicine’ https://www.uclh.nhs.uk/our-services/find-service/integrated-medicine accessed 24 November 2024.

[42] University College London Hospitals, ‘Royal London Hospital for Integrated Medicine’ https://www.uclh.nhs.uk/our-services/our-hospitals/royal-london-hospital-integrated-medicine accessed 24 November 2024.

[43] Jason Cheah, Wong Kirk-Chuan and Harold Lim, ‘Integrated care: from policy to implementation – The Singapore Story’ (2012) International Journal of Integrated Care.

[44] Goh Chye Tee, ‘Commentary: Where does traditional Chinese medicine fit into Singapore’s healthcare reform plan?’ Channel News Asia (Singapore, 29 November 2022).

[45] Salma Khalik, ‘Family doctors can become specialists; electronic health records to be compulsory’ The Straits Times (Singapore, 26 August 2024).

[46] Sabrina Ng and Jalelah Abu Baker, ‘Some major TCM chains call for access to national medical records to better help patients’ Channel News Asia (Singapore, 5 November 2024).

[47] Wen Qiang Lee and others, ‘Factors influencing communication of traditional Chinese medicine use between patients and doctors: A multisite cross-sectional study’ (2019) Journal of Integrative Medicine 396.

[48] Hong Zhang and others, ‘On standardization of basic datasets of electronic medical records in traditional Chinese medicine’ (2019) Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 65.

[49] Towards an Integrated Health Information System in Korea (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, 2022) https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/towards-an-integrated-health-information-system-in-korea_c4e6c88d-en accessed 24 November 2024.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Neo Chai Chin, ‘The Big Read: Big data making a great difference in healthcare’ Today (Singapore, 28 February 2015).

[52] Milawaty Nurjono and others, ‘Implementation of Integrated Care in Singapore: A Complex Adaptive System Perspective’ (2018) International Journal of Integrated Care 1.

[53] Chuan De Foo and others, ‘Healthier SG: Singapore’s multi-year strategy to transform primary healthcare’ (2023) The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific.